I have put off writing about this for a while, as I feel certain that I can’t sufficiently describe both the experience of going on safari, nor the deep and lasting impact that the African bush and wildlife has left on me. I also have concerns that any photographs I post to accompany this chapter will be inadequate, since wildlife photography has improved drastically in recent years thanks to the digital revolution.

GAME PARKS

I would prefer the term ‘reserve’ to ‘park’ as the term ‘game park’ implies a small rather domestic zoo, such as in common in some former country houses in Britain. Game parks in Kenya are vast. Only Nairobi park has a fence on two sides to stop wildlife from wandering into the city. The boundaries and territory of the game parks are rigorously patrolled against poaching, which over the years has devastated the elephant population, and brought near extinction to some species. A big programme of education was brought in during the 1970s as the demand for land encroached on the space that the wildlife required. Understandably, local farmers were keen to shoot elephants that would trample through their precious crop, and elephant can destroy a field on maize in no time at all.

The most famous one, Tsavo is divided into two sections, East and West and covers around 22,000 sq km. Wales, by comparison is 20,767 sq km. Other game parks include the similarly famous ‘Masai Mara’, Samburu in Northern Kenya, and Amboseli near the Tanzanian border.

Each game park has a lodge, (hotel) for the tourists, one of the most famous being ‘Treetops’ near Mount Kenya which is where the young Princess Elizabeth became queen, when her father King George V died whilst she was on tour in Kenya. The lodges are built around a watering hole, which has a salt lick for wild animals, and some like ‘The Ark’ feature an underground passage to a hide, just yards from the waterhole. To sit in an evening watching elephants come to drink whilst the sun goes down is an experience that is simply out of this world. After dark, under carefully dimmed spot lights, it is the turn of the nocturnal animals. Early morning and early evening, ‘game drives’ accompanied by local African game wardens, are undertaken to spot lion, cheetah or sometimes rarely leopard. The animals would most often rest up in the midday sun.

That is the experience of the tourist. As locals, we adopted a different approach preferring to stay in small self catering ‘bandas’ (small huts). In this way we could avoid the tourists, whose noise, cameras and mini buses were a huge frustration to us if we encountered them. The wildlife and the endless miles of bush remained the same but the experience of being on safari was so much richer.

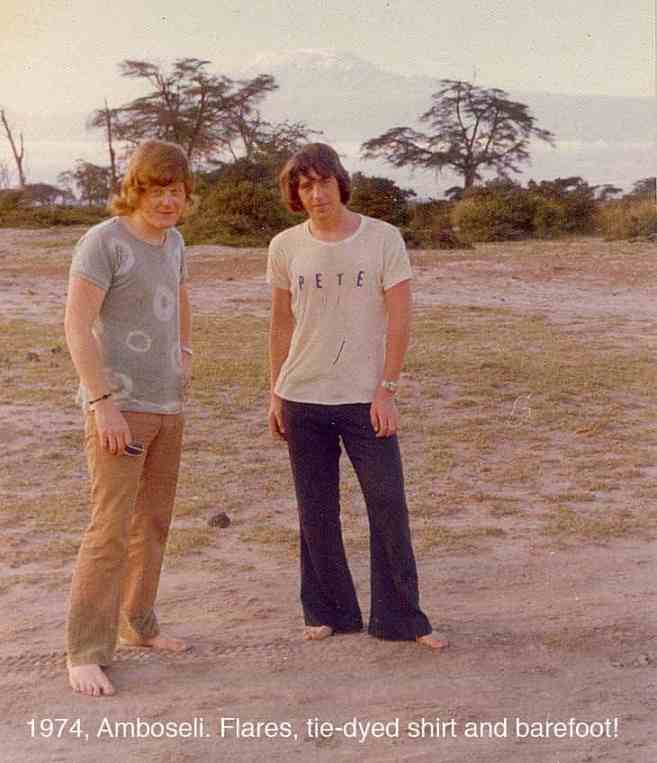

I had two favourite locations, Ngulia in Tsavo and Amboseli which offers spectacular views of Mount Kilimanjaro, the highest free-standing mountain in the world, and largest in Africa.

To reach Amboseli it was necessary to drive very many miles over a dried up lake. We had a land rover with a sun hatch, so it was always fun standing on the back seat and being driven whilst leaning out the hatch. Amboseli offers some of the best opportunities to see African wildlife because the vegetation is sparse due to the long dry months. This in addition to the low rainfall experienced in the area (11 inches per annum on average), means that animals frequent the swamp land surrounding the river.

There wasn’t any electricity in the majority of the camps, was either done on a ‘kooni’ (wood) stove or gas. We usually took curry or stew which could be easily heated up, although a few locations employed a cook. Some camps had flush toilets but the vast majority were ‘long drops’. At night, each person had a paraffin lantern, which they took to bed. Hearing lion roar and cough at night, whilst you are sleeping under mosquito nets, is strangely comforting. In the morning, you could see lion or cheetah paw prints in the dust around the camp. The sublime experience of sitting on a veranda outside your banda, and gazing into the distance, watching a line of elephant walk slowly to a watering hole is something that is difficult to put into words.

On one occasion at a camp, a local African said that there was an elephant at the end of the line of bandas. We all crept along to see, and rounding the last hut came face to face with a large bull elephant. African elephants are not to be messed with, and are very dangerous. The elephant turned raised it’s trunk in a bellow and frightened us so much, the African lad climbed a nearby thorn tree is seconds. It’s not called a thorn tree for no reason, all the branches are covered in inch long sharp thorns

Another time David and I were on our own in Tsavo. We had hit a ditch too hard in the Landover and broken the half shaft. This meant we could only drive in first or second gear I think. We knew we wouldn’t get back to Nairobi that day and would have to spend another day in Tsavo. Using the radio phone, the Tsavo game warden phoned the Nairobi game warden, and the call was then transferred to the Nairobi exchange. The line, which was never good at the best of times, was so bad that my father wasn’t able to understand us, but knew we were phoning to say something had gone wrong. He said, ‘if you are staying another night, put the phone down’, which we did. (Generally the phone lines were always bad, as the copper wire was often looted to make bangles to sell to the tourists).

Other memorable trips included Lake Baringo with our friends, the Jones family. Lake Baringo is, after Lake Turkana, the most northern of the Kenyan Rift Valley lakes. The lake is fed by several rivers and has no obvious outlet; the waters are assumed to seep through lake sediments into the faulted volcanic bedrock. It is one of the two freshwater lakes in the Rift Valley in Kenya, the other being Lake Naivasha. It lies off the beaten track in a hot and dusty setting and over 470 species of birds have been recorded there, occasionally including migrating flamingos. African birdlife is simply stunning and we took watching birds as seriously as watching the wildlife.

During various safaris we have been chased by rhinos and seen lion stalk and kill antelopes, watched baby lion cubs play and observed the seemingly cruel hand of nature at very close quarters, privileged onlookers to a world much older than ours. Experiences so precious that it brings tears to my eyes as I type, just recalling them. I have always been extremely grateful for the privilege of being able to experience this aspect of Kenya, during what was probably its golden age.

The wild scrub land is on a scale that is breathtaking and somehow the silence and lack of civilisation, along with observing wildlife in their natural habitat reconnects your soul with the wonder of the world. There is a part of me that will forever remain, left behind in the African bush. It was so deeply formed my character in a way that is hard to explain and so often my heart longs just to be back there. I am so grateful that I married someone who had this experience so deeply engrained in her soul; it has made the ache that I feel for the place so much more bearable.

You must be logged in to post a comment.